exhibition

01 October 2021 > 21 August 2022

Sebastião SalgadoAmazônia

the exhibition’s closing has been extended to Sunday 21 August 2022

gallery 4

curated by Lélia Wanick Salgado

valid until 9 April due to the Museum’s first-floor closing

buy online

the only open ticket, valid for 100 years, for one admission to the Museum and all current exhibitions

buy online

valid for access to the Museum during the last opening hour, available online and at the Museum’s digital ticket point only

upon presentation of the membership Card or Carta EFFE

buy online

minors under 18 years of age; disabled people requiring companion; EU Disability Card holders and accompanying person; MiC employees; European Union tour guides and tour guides, licensed (ref. Circular n.20/2016 DG-Museums); 1 teacher for every 10 students; ICOM members; AMACI members; journalists (who can prove their business activity); myMAXXI membership cardholders; European Union students and university researchers in Art and Architecture, public fine arts academies (AFAM registered) students and Temple University Rome Campus students from Tuesday to Friday (excluding holidays); IED – Istituto Europeo di Design professors, NABA – Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti professors, RUFA – Rome University of Fine Arts professors; upon presentation of ID card or badge – valid for two: Collezione Peggy Guggenheim a Venezia, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Sotheby’s Preferred, MEP – Maison Européenne de la Photographie; on your birthday presenting an identity document

for groups of 12 people in the same tour; myMAXXI membership card-holders; registered journalists with valid ID

buy online

under 14 years of age

buy online

disabled people + possible accompanying person; minors under 3 years of age (ticket not required)

book online

MAXXI’s Collection of Art and Architecture represents the founding element of the museum and defines its identity. Since October 2015, it has been on display with different arrangements of works.

the exhibition’s closing has been extended to Sunday 21 August 2022

gallery 4

curated by Lélia Wanick Salgado

Arcipelago fluviale di Mariuá. Rio Negro. Stato di Amazonas, Brasile, 2019.

Only from space can one grasp the sheer scale of the Amazon forest. It covers nearly a third of the South American continent, an area much larger than all of Europe. Through this extravaganza of nature flows the Amazon River, fed by some 1,100 tributaries, including 17 over 1,500 km (930 miles) long. Each day, it disgorges – some 17 billion tons of water – 20% of the world’s freshwater into the Atlantic Ocean.

Seen from a plane or a helicopter, the rainforest resembles a vast green carpet decorated with the twisting and curling lines of slow-moving rivers. In the wet season, this tidy tapestry is disrupted as rivers overflow their banks, in places flooding 100 km (60 miles) into the forest, in others creating lakes and lagoons, only to return to their previous paths once the waters recede. So flat is this landscape that at Tabatinga on Brazil’s western border with Colombia, the Amazon River is only 73 m (240 feet) above sea-level – and still 4,660 km (2,900 miles) from its mouth.

Yet this natural cycle, which has played out time and again for millions of years, is now in peril. Deforestation is accelerating, most ferociously on the peripheries of the jungle, with new roads constantly drawing streams of migrant farmers, loggers and miners. For the most part, this is taking place on publicly owned land, while in Indigenous lands and national parks, only a small part of the forest has so far been razed.

Nonetheless, with at least 17.25% of the biomass already destroyed, the fear is that deforestation may soon reach “a point of no return” – a state from which the biome cannot recover, turning vast areas of forest into tropical savannas.

photo: Arcipelago fluviale di Mariuá. Rio Negro. Stato di Amazonas, Brasile, 2019 © Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto

Rio Jutaí. Stato of Amazonas, Brasile, 2017.

One of the most extraordinary – and perhaps least known – features of the Amazon rainforest is a phenomenon known as “flying rivers”. Forming above the Amazonian jungle, these moisture-laden «aerial rivers» extend over a large part of the South American continent. Each day, the Amazon River pours 17 billion tons of water into the Atlantic Ocean, but scientists estimate that the volume of water moved by the region’s flying rivers is even greater: 20 billion tons of water per day rise into the atmosphere from the rainforest, aptly dubbed the “Green Ocean”.

Most remarkable, though, is the sheer scale of this phenomenon. A large tree can suck water from as much as 60 m below the ground and produce as many as 1,000 liters of water per day. And since this is repeated by 400 to 600 billion trees, it is easy to see how the Amazon forest generates a large percentage of the water that it later receives as rain. In fact, even the humidity that reaches the mainland through evaporated sea water is itself quickly recycled by the jungle in a process known as “evapotranspiration.”

The “flying rivers” are vital to the well-being of tens of millions of people, primarily in Brazil. They also impact weather patterns across the globe and are themselves vulnerable to the effects of deforestation and global warming. In both cases, what happens in the Amazon is a key variable. Scientists believe that, as a result of accelerated deforestation and climate change, the groundlevel temperature of the basin has already risen by 1.5o C and is set to rise a further a 2o C if current trends continue. Similarly, they fear a drop in annual rainfall of between 10 and 20% as a result of global warming.

photo: Rio Jutaí. Stato of Amazonas, Brasile, 2017 © Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto.

Rio Negro. Stato di Amazonas, Brasile, 2019.

Clouds play a leading role in the never-ending drama of the Amazonian ecosystem. They can be small or large, friendly or threatening, but from a boat on a river or a plane in the sky, they are always in view. Even in the forest, where vegetation may block them from sight, there are frequent reminders of their presence: before each day is out, heavy rain is more than likely. And since weathering a tropical storm can be as perilous as it is terrifying – for their own safety, anyone spending time in the region, must learn to read the clouds as astutely as they would a topographic map. Over the Amazon rainforest, rare is the day when the sky is a perfectly clear blue or a blanket of solid grey. Cloud formations offer an ever- changing spectacle. It begins in the morning when warm moist air rises from the jungle and encounters tiny particles which condense the vapour into water droplets, creating little cotton-ball clouds known locally as aru. As the day advances, these small clouds rise and join together and, temperature and wind speed permitting, gather the strength to become a storm cloud known as a cumulonimbus.

This is by far the most dangerous meteorological formation, reaching heights of several thousand meters and capable of producing hailstones and winds of up to 200 kph (125 mph), and hurling lightning bolts and fierce precipitation onto the jungle. Such is its force that even large aircraft will seek at all cost to avoid it, helicopters will immediately look for a clearing where they can land, and river boats will rush to find shelter. On rare occasions, as most recently in 2005, a storm can be so devastating that it can leave thousands of flattened trees in its wake.

photo: Rio Negro. Stato di Amazonas, Brasile, 2019 © Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto

Monte Roraima. Stato del Roraima, Brasile, 2018.

The Andes, the mountain range that governs the life of the Amazon Basin, lies far to the west of Brazil. The Imeri, the largest mountain range within Brazil, provides a natural border with Venezuela in the far north of the state of Amazonas. Its highest point is the sharply pointed Pico da Neblina, or Mist Peak, which at over 3,000 m (10,000 feet) is Brazil’s tallest mountain. As its name suggests, it is often shrouded in clouds, making it a perilously slippery mountain to climb. Not far away, the Pico 31 de Março is almost 2,900 m (9,500 feet) high. And in the same region, the Pico Guimarães Rosa, named after a renowned Brazilian writer, stands 2,105 m (7,000 feet) above sea-level. What is striking about these mountains is the rainforest that carpets their lower slopes, with vegetation gradually thinning out until it is halted by sheer rock.

To the east in the state of Roraima, Mount Roraima, which belongs to the Paracaima mountain range, is dramatically different geological formation. Rising to 2,800 m (9,000 feet), this table-top mountain standing on the border with Guyana and Venezuela belongs to a category called tepuis, home to endemic plant and animal species.

The Serra do Aracá State Park protects a mountain range of exceptional beauty. Located about 400 km (250 miles) northwest of Manaus, its rugged structure is again largely made up of tepuis and, while rising to only a maximum of 1,700 m (5,600 feet), it stands out dramatically against the jungle. It is also here that Brazil’s highest waterfalls are found, Eldorado and Desabamento, with water plunging 360 m (1,180 feet) against a bare mountain façade.

photo: Monte Roraima. Stato del Roraima, Brasile, 2018 © Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto.

Rio Jaú. Stato di Amazonas, Brasile, 2019

For centuries after Portugal colonized Brazil, the Amazon was called the “Green Hell”, an impenetrable rain-sodden jungle that offered nothing but danger to outsiders. Those who ventured into it and survived to tell the tale became famous for their accounts, such as Spanish conquistador Francisco de Orellana and German explorer Alexander von Humboldt, along with Theodore Roosevelt and Marshall Cândido Rondon, a Brazilian army cartographer, considered the greatest protector of the Indigenous people of Brazil in the 20th century. But many expeditions, such as those hoping to find gold in the mythical lost city of El Dorado, never returned. While some explorers may have been killed by hostile native groups or died of snake bites or starvation, a surprisingly large number chose to settle down with Indigenous peoples and share in their bucolic way of life.

Today, the rainforest is viewed more positively, sometimes even romantically. It is thought of as a Green Paradise, an extraordinary natural heritage, with one of the planet’s highest concentrations of botanical species, including some 16,000 species of trees and innumerable plants with remarkable medicinal properties. Further, with its unparalleled density of vegetation it absorbs greenhouse gases and breathes out oxygen.

For Indigenous communities, rivers provide their main high-protein foods, but they know to keep a safe distance from natural floodplains, where the overflow in high water season can cover up to 100 km (60 miles). Most of this water comes from snow-melt and rain in the Andes. The resulting flooding is a constant reminder that much of the Amazon Basin once lay under the sea.

photo: Rio Jaú. Stato di Amazonas, Brasile, 2019 © Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto.

Anavilhanas, isole boscose del Río Negro. Stato di Amazonas, Brasile, 2009

In the vastness of the Amazon rainforest, an age-old battle between land and water has spawned the world’s largest fresh water archipelago, known as the Anavilhanas, with islands of every imaginable shape rising out of the dark waters of the Rio Negro. From the sky, it is an astonishing sight, stretching as far as the eye can see. From the river, it is an immense puzzle, through which only experienced boat captains can chart routes ensuring safe passage between myriad natural obstacles.

Most of the larger islands are themselves covered with dense tropical vegetation. The number of islands, estimated between 350 and 400, is difficult to count precisely because smaller low-lying islands may temporarily or even permanently disappear when the rainy season raises the water level by over 20 m (65 feet). Thus, from year to year, satellite photographs illustrate the constantly changing formation of the archipelago.

The first islands of the Rio Negro appear about 80 km (50 miles) north-west of Manaus. They stretch in two major sections some 400 km (250 miles) upstream as far as Barcelos, the first town founded by the Portuguese settlers who arrived by sailing ship in the mid-18th century. The first section, around 135 km (85 miles) long, where the river averages 20 km (12 miles) in width and the islands occupy 60% of its surface is now protected as the National Park of Anavilhanas. Covering an area of 350,470 hectares (866,000 acres), the park is entirely uninhabited except for the small town of Novo Airão on its west bank, 180 km (112 miles) north-west of Manaus.

photo: Anavilhanas, isole boscose del Río Negro. Stato di Amazonas, Brasile, 2009 © Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto

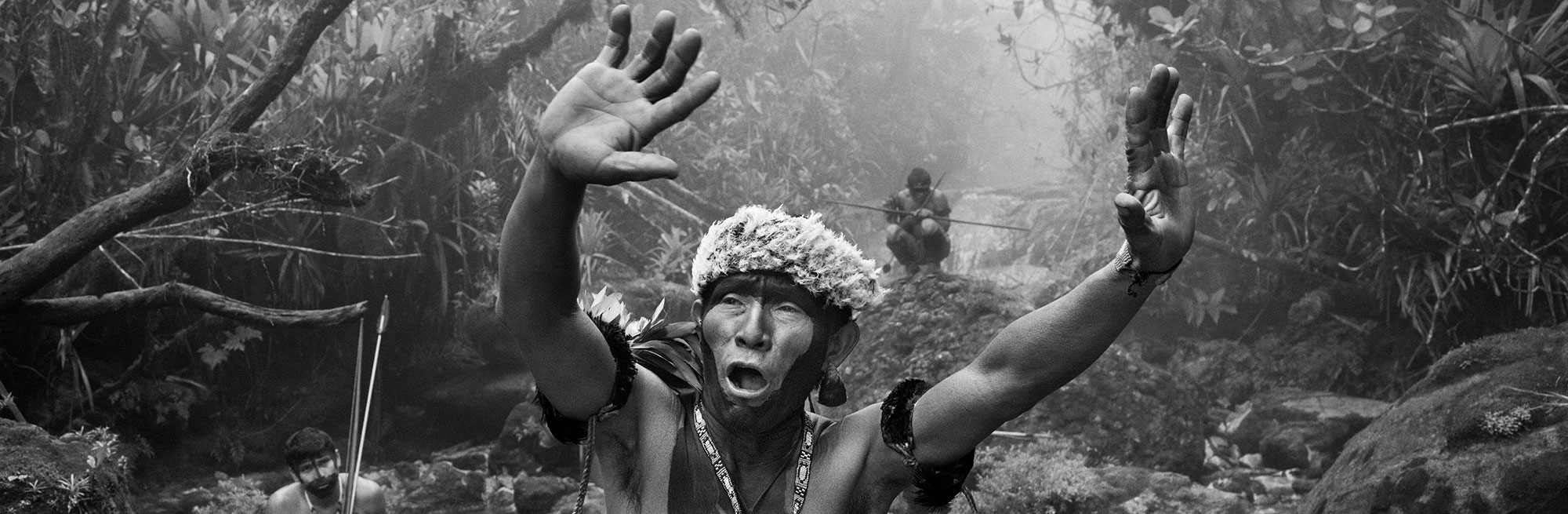

For six years Sebastião Salgado travelled in the Brazilian Amazon, photographing the forest, the rivers, the mountains and the people who live there.

This exhibition, premiering in Italy with more than 200 photographs, plunges us into the Amazon rainforest, uniting Salgado’s impressive images with the sounds of the jungle. The rustling of trees, the cries of animals, birdsongs or the roar of water pumbling down from mountain tops, having turned into a magical soundscape, by the composer Jean-Michel Jarre.

The exhibition highlights this ecosystem’s fragility, showing how in protected areas, where indigenous communities, ancestral guardians of the environment, lives in territories where the forest has suffered almost no damage. Salgado invites us to see, listen and reflect on the ecological situation and how people are addressing the crisis today.

header: Yanomami shaman talking to the spirits before climbing Mount Pico da Neblina. Amazonas State, Brazil, 2014.

sezioni di mostra

The Amazon seen from above

Watering the entire continent

When it rains in the rainforest

Unexpected uplands in the lowlands

A source of fear and inspiration

Islands in the stream